Welcome back — it’s the end of the year, the weather’s getting cold, so stay warm.

This issue is about one specific skill: integrated note taking It is not a productivity trick. It is a way to encode knowledge so you can actually retrieve it later and use it to solve problems.

1) The simplest model of learning: goal → encode → retrieve

Learning is always about moving you toward a goal. Sometimes the goal is obvious (finish a project). Sometimes it’s fuzzy (become “better” at something). Either way, a useful learning system has two parts:

- Non-learning: self-management + mindset (energy, focus, emotions, consistency)

- Learning: how knowledge gets built and used

Inside the learning part, there are two processes:

- Encoding: how you process and store what you consume

- Retrieval: how you recall and apply it to real problems

Most people focus on consuming more information. But the real leverage is usually encoding—because encoding determines whether anything becomes usable later.

2) What encoding really is (and why it’s not “more notes”)

Encoding is what you do with information while you watch, read, or listen.

It’s not copying. It’s not highlighting. It’s not transcribing.

Encoding is the act of shaping information into a form your brain can store, locate, and later apply. That means encoding starts with “opening the black box”—reflecting on what’s happening in your thinking.

This is where metacognition comes in.

Notice confusion, resistance, excitement, or overwhelm as part of the learning process.

These feelings are not evidence that you’re failing.

Then you ask: How does this fit into what I already know?

Because “fit” is what turns information into something your brain can actually keep. Fit means: where does this belong, what does it connect to, and what is it for? If you can’t answer that, the idea has nowhere to live—so it never becomes usable.

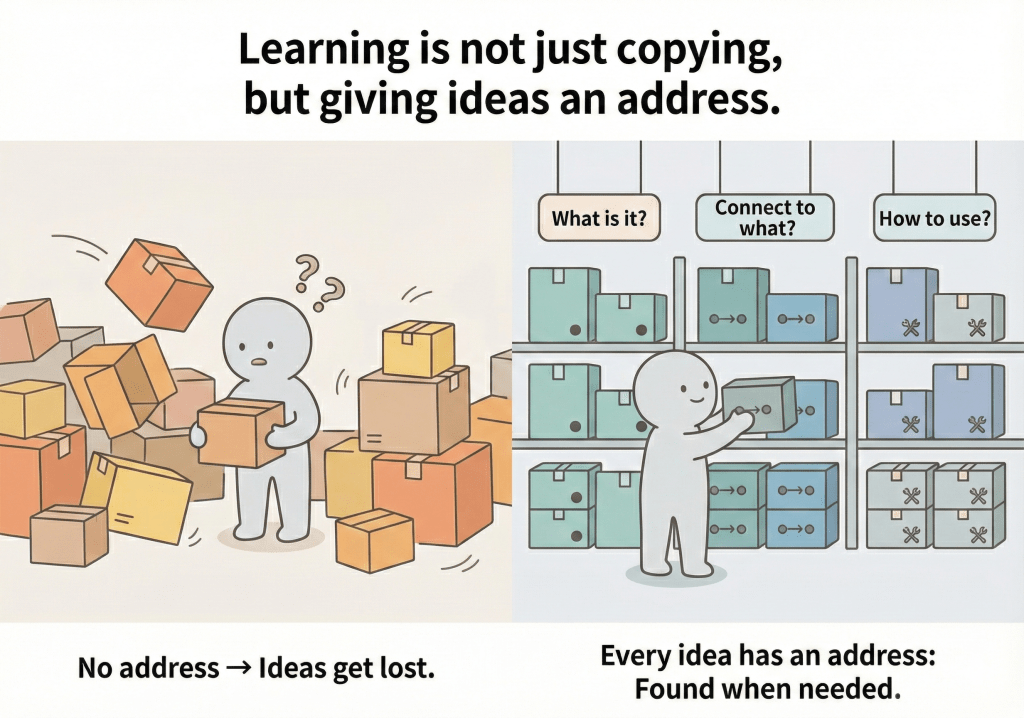

A simple way to understand encoding is: encoding = giving an idea an address.

3) The warehouse analogy: why unorganized knowledge disappears

Here’s the mental model.

Your brain is like a warehouse. Knowledge is like packages.

When you need to use something later, you’re trying to retrieve a package to deliver. But retrieval only works if the package has an **address, **a classification, and a place in the system.

If information comes in with no address—no category, no relationship, no purpose—your brain doesn’t know what to do with it. And because attention and memory are expensive, it tends to discard it.

So the core job of encoding is:

Give knowledge an address.

Not perfect notes. Not more notes. An address.

4) Schemas: the “big shelves” that make your brain special

To avoid micromanaging every package, your brain builds large schemas—big organizing structures that hold many smaller ideas.

And these schemas aren’t static. They change as you learn. They’re more like transformers: gradually reshaping and reorganizing to match the problems you’re trying to solve.

That’s what makes the human brain special: it doesn’t just store information. It can manipulate structure—rearrange meaning, build relationships, and adapt the internal model to the situation.

This is also the key difference in your AI workflow.

NotebookLM and GPT can summarize information and suggest questions. That’s helpful. But they don’t have access to your lived context and prior knowledge.

Your brain does have this access. They can’t build your internal schema for you.

Encoding is personal. Structure is personal.

5) From linear notes to Level 3 nonlinear notes

Most people start with linear note-taking: writing left to right, line by line. It’s simple, and it feels productive, because you can “capture” a lot.

But linear notes often don’t encode well. They store information as a timeline, not as a system. And when you need to retrieve it later, you can’t find it—because nothing has an address.

Level 3 nonlinear note-taking is the opposite approach:

You use questions to force structure.

Instead of asking “What did they say?”, you ask:

- How does this connect?

- Why does this work?

- What problem does this solve?

- How would I apply it this week?

- What’s the smallest chunk of this idea I can name without losing the meaning?

- What category (shelf) does this belong to in my warehouse — and what label would I actually search for later?

- What other chunks should live next to it (examples, constraints, steps), so it becomes retrievable and usable?

This is also why Level 3 tends to look like mind mapping or relational notes: you’re not writing a transcript. You’re building a network of relationships that your brain can navigate later.

7) The secret: Level 3 is recursive, not linear

Beginner mistake: treating Level 3 like a one-pass workflow.

Level 3 is a recursive loop. You repeat it until the layers underneath the topic become stable.

You move up and down three layers:

- Topic layer: what the idea is, what the terms mean, what’s being claimed

- Logic layer: what connects to what and why (mechanisms, tradeoffs, constraints)

- Bottom layer: what it means for you (your prior knowledge, your project, the action you’ll take)

You don’t go topic → logic → bottom once.

You bounce.

Topic → logic → topic again because you missed something.

Logic → bottom → logic again because application exposes a gap.

Bottom → topic again because you need another input to stabilize the structure.

The movement is the process.

9) What Level 1–3 feels like (and why it gets hard)

If you’re new to nonlinear notes, it helps to name what the progression actually feels like.

This is because the struggle is often emotional, not intellectual.

Level 1: Isolated/linear capture

You’re mostly transcribing: left to right, line by line.

It feels clean and safe. The struggle shows up later. When you try to use the notes, you can’t find what matters. This happens because the ideas never got an “address.”

It’s easy to mistake volume for encoding.

Level 2: Connected / occasional sparks

You start seeing 1–2 relationships here and there—“oh, this connects to that.” You get light bulb moments occasionally. The struggle is inconsistency. The connections are real but scattered. You don’t yet have a stable structure to hang them on.

Level 3: Integrated / lots of light bulbs (but messier)

You’re building an internal structure, not collecting facts.

You get more frequent light bulb moments because each connection makes the next connection easier to see. The struggle is that it feels recursive and out of order. This is where overwhelm can spike, and where the urge to escape (freeze / avoid / rabbit-hole) shows up.

And the “caveman era” joke is basically about threshold concepts.

These are moments where you cross a line. You can’t unsee the structure anymore. Same cave… upgraded wiring.

(Next section: the real difficulty—overwhelm and the urge to escape.)

10) The real difficulty: overwhelm and the urge to escape

For most people, the hardest part isn’t the note format.

It’s the feeling of overwhelmingness.

When you do relational thinking, it can feel recursive and messy. It often requires learning out of order. Under high cognitive load, overwhelm can feel like anxiety and danger—like you want to run away, freeze, avoid, or repress it.

And that’s when tool-suggested rabbit holes become tempting: they feel like progress, but they can become escape.

The first move is simple, but not easy:

- acknowledge it

- accept it

- label it

Emotional regulation under high cognitive load is its own topic—and it’s also where I personally got stuck. We’ll talk about it separately.

8) A beginner-friendly Level 3 loop (repeat until it clicks)

Here’s a simple question-driven loop. Don’t try to do it perfectly—just run it, and then run it again.

- Set the address (goal + context)

What am I trying to accomplish with this learning session? What project or decision does it serve? - Open the black box (metacognition)

What am I noticing—confusion, resistance, excitement, overwhelm? What am I tempted to do (escape, rabbit-hole, copy notes), and why? - Extract what might matter

What’s the one idea here that could change how I act this week? If I keep one sentence, what is it and why? - Link to existing schema

What does this remind me of? Where does it fit—confirm, extend, or contradict what I think? - Name the relationship (logic layer)

What’s the relationship—cause/effect, tradeoff, sequence, constraint, analogy? What’s the most meaningful connection for my goal? - Force application (bottom layer)

How would I use this in the next 7 days? What’s the smallest test that proves it matters? - Stress-test retrieval

If I had to explain this without looking, what would I say? What would I do differently tomorrow if I truly believed it? - Close the loop (next question + stop rule)

What’s the next question that serves the goal (not curiosity-for-escape)? When do I stop?

(Example stop rule: When I have one test and one next step.)

Level 3 nonlinear note-taking isn’t about prettier notes. It’s about encoding—giving knowledge an address in your warehouse, building schemas that can evolve, and creating structures your brain can actually manipulate to solve problems.

Tools can help, but they can’t steer. You’re the one building the system.

Thanks for reading. See you in the next issue.

Leave a comment